Federal agents are warning leaders at top universities to be on the lookout for foreign spies or potential terrorists trying to steal their research.

The Boston Globe

I was sitting in my office, trying to concentrate on raw data for a monograph I was writing on Wallace Stevens. It seemed to me I had found a link between his use of alliteration–say, “Gloomy grammarians in golden gowns”–and the surety bonds issued by his day job employers–Hartford Accident, American Bonding, Equitable Surety. “Wink most when widows wince,” for example, was written the day after he settled a major claim by the Wainwright Wrecking Company for pennies on the dollar. Curious, I thought, and perhaps the sort of apercu that would finally bring me tenure!

A knock-dammit, this always happens. Probably some kid complaining about his score on the mid-term. I steeled myself for the usual irruption. I know that’s how you feel about the poem, but what’s important is what it means–if anything.

I opened my door, prepared to point to my office hours posted there-Tuesdays and Thursdays, 10 to 11 during months with “r’s”, third Wednesdays during the summer except August, when I’m available only by mail to a P.O. Box in Truro, Mass.

“What?” I barked with annoyance, as my eyes drifted downwards to–Rasha Wabe, a transfer student from Lebanese International U. She had deep brown eyes like dates but with irises, and a figure I couldn’t figure out because she dressed so modestly.

Kowa-bunga!

“Ms. Wabe–I really can’t see you now.”

“Oh, but you must! I simply do not understand this Wallace Stevens man–he is driving me to tears.”

I looked up and down the hall. I didn’t need a crying female student on my curriculum vitae.

“All right-come in.” I motioned her inside and she took a seat in the chair beside my desk where students sat if they ever caught up with me.

I offered her a cup of chamomile tea and she calmed down a bit.

“Now, what is your problem with Stevens?” I asked skeptically. I figured she was just looking for an extension on her term paper.

“‘Chieftan Iffucan of Azcan in caftan of tan with henna hackles, halt!’ What on earth can that mean?”

Stevens: “My job is boring–I think I’ll write some incomprehensible poetry to break the tedium.”

“It may not ‘mean’ anything,” I said cooly. “On the other hand, maybe it does.”

“Well, that is no answer when one has to write a twenty-page paper!”

So it was the term paper.

“There is much that can be said–and not said–about that line,” I mused cryptically as I consulted my bibliography; Bantams in Pine-Woods, 1923, during Stevens’ Hartford Accident years.

“But what can I say-I don’t understand it.”

I flipped through the defendant table of the docket of the Hartford County Superior Court for that year. AAA Construction Co., Abacus Heating & Cooling. Az-Can Aluminum Co.

“Aha!” I exclaimed.

“What?”

“I think I’ve found something.”

She stood up and came around behind my chair.

“What is this?”

“It’s a key to understanding the nonsense in Stevens.”

“But if you make sense of it, it isn’t nonsense any more–is it?”

She had a point, although by the Honor Code of the American Association of University Professors, I wasn’t allowed to admit it.

“Sort of–but it’s still poetry.”

I turned around as I said this and saw that she had discarded the burqa and was now wearing the minimalist rags in which raqs sharqi–or, to lapse into Orientalisms, the Dance of the Seven Veils, the Hoochy-Koochy–is performed.

“Ms. Wabe,” I said with more than my usual reserve. “This is a breach, real or imminent–”

“‘Imminent’–two i’s–or ‘immanent’–one i one a?”

“Two i’s–of our Code of Student-Professor Relations.”

“What did Yeats say? You can’t tell the dancer from the dance?” she said with a flirtatious air.

Yeats: “I can’t tell the dancer from the dance, so go ahead and shake that thang!”

“I don’t think that will help me when your parents get wind of this.”

“It is understood that I may indulge in petty license during my undergraduate years here in The Great Satan-especially if it helps me bump up my G.P.A.”

She was cool. Probably had an arranged marriage set up for her back home. Getting out of this mess would require all the deconstructionist skills I had learned at the State University of New York-Plattsburgh Avant-Garde Summer Refresher Course.

“Why don’t you save your routine for multi-cultural night at the Student Union?”

“No–the raqs sharqi is performed privately, before one’s beloved.”

Ai-yi-yi. I glanced down at my grade-book. Wabe, Rasha. 3.32. All this to move from a B to a B+? The belly dance would just be the camel’s nose under the graduation day tent.

“Listen, Rasha,” I said.

“Yes?”

“I’ve enjoyed your little dance. Suppose I let you in on a little secret, so we don’t end up trading favors of a more illicit sort?”

“That would be most satisfactory, O infidel professor.”

“Take a look at this,” I said, as I pointed to two lines in “Nomad Exquisite”:

So, in me, come flinging Forms,

flames, and the flakes of flames.

“I’m flummoxed by it,” she said.

“Published in 1923. Now look at this list of counsel who opposed Stevens when he appeared in court for the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company from 1920 through 1922.” I let my finger slide down the roster of names until it hit the f’s.

“Frank A. Filbert, Esq., Filbert, Frost & Farner,” she read.

“Are you starting to see a pattern?” I asked.

“Hmm. What kind of offices did the ‘F’ boys’ have?” she asked cryptically.

“Silent, upon a peak in Darien.”

“This is most interesting,” she said. “I think I’ll return to my carrel and get to work. Thank you ever so much for the tip.” From terpsichorean temptress to sorority sweetheart, just like that.

She started to re-robe when the door flew open.

“Homeland Security,” yelled a young man in a police-blue jumpsuit, a sidekick standing behind him. “Drop the rhyming dictionary and nobody gets hurt.”

“Aren’t you supposed to read us our rights before you yell at us?” I complained.

“Not if you haven’t signed the Geneva Convention.”

“I went to the Modern Language Association’s 123rd convention in Chicago last December.”

“Plenary session, forum or workshop?”

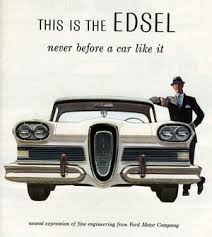

“Special session. ‘Marianne Moore, Poetess of the Ford: How the Edsel Disaster Could Have Been Avoided by Naming It ‘Utopian Turtletop’.”

Moore and Edsel: “It looks like an Oldsmobile that sucked a lemon.”

“Utopian Turtletop?”

“Moore’s suggestion.”

“Okay. What about her?” He nodded at Rasha. She was fully-clothed by now, which meant that only her big brown eyes were visible through a slit in her burqa.

“Her? She’s a student here.”

“That’s what they all say. Lemme see something she’s written.”

Rasha complied, handing over her notes and outline for the paper on Stevens.

“What is this,” the anti-terror gendarme demanded. “‘Chieftain Iffucan of Azcan in caftan’- it doesn’t make any sense.”

“I can explain,” I began.

“Don’t bother. I know undergraduate gibberish when I see it,” he said as he and his partner turned to go. “What’s worse,” he said over his shoulder, “You’ll probably give her a A for it.”

Available in print and Kindle format on amazon.com as part of the collection “poetry is kind of important.”