It’s a cool spring day and I’m sitting in Quincy Market, Boston, Ground Zero for the Boston singles scene. At an age that qualifies for Social Security I’m decidedly out of place, but less so than the guy I’ll be meeting for lunch: Sebastian Brant, author of the original “Ship of Fools,” who shuffled off to the afterlife in 1521. At the age of 501, he’s going to make me look like a spring chicken, so I hope to outshine my wingman . . . in case we get lucky.

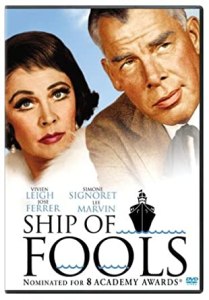

We’re both published authors, but the Brant-Man has me beat by a mile. Ship of Fools first appeared in 1494 and dominated the best seller lists for centuries because there was so little competition, despite what it says in the Book of Ecclesiastes 12:13 (“the writing of many books is endless”). Your choices when you went to the book rack in Ye Olde Drugge Store back then were basically the Bible, Latin grammar books, and Ship of Fools. It’s been novelized by Katherine Anne Porter, made into a major motion picture with Lee Marvin and Vivien Leigh, even inspired a song by former Led Zeppelin singer Robert Plant, but Brant didn’t get a nickel out of any of those exploitations of his work. He’s been reluctant to sue since he may have cribbed the concept from Plato, who used the allegory of a ship with a dysfunctional crew in Book VI of his Republic. For reasons not entirely clear to me, Plato gets a pass among liberal arts types even though that dialogue makes a North Korean prison look like a summer camp for dance and theatre.

The waiter asks how much longer the other member of my party will be; there’s a line of yuppies standing at the maitre d’s station, and he’s hoping to turn the table quickly, but I let him know I’m not going anywhere until I get to know the guy whom I like to think is my brother from another mother, there are so many curious parallels between our lives. He studied philosophy, I studied philosophy. He studied law, I studied law. He wrote “worldly” poems that “knew little of, and cared less for,” the conventional poetry that preceded him, in the words of Edward H. Zeydel, and he was thus “forced to cast about for novel subjects of contemporaneous interest.” I had the same problem, and as a result have written poems about Fritos, the iconic snack made by deep-frying extruded whole cornmeal; tow truck drivers; even Chauncey Billups, the former Boston Celtics guard traded away in an ill-advised move after only one season, who went on to become a five-time NBA All-Star and earn the nickname “Mr. Big Shot.”

Even closer to the bone, however, was his shift to “fliegende Blatter,” short satiric broadsides or lampoons published in pamphlet form, describing a recent event but always with a moral that reflected his philosophy of life. That’s right–Brant was a blogger before the internet was invented! As a result, I have a small quiet corner in my heart that recognizes him as my spiritual and literary forebear.

I look up from my reverie and see a man in clothes that wouldn’t be out of place at one of our region’s faux-Medieval faires, and figure it’s got to be him.

“Sebastian–over here!” I call out, then say to the waiter “Why don’t you bring us a bottle of German wine, a precocious gewurztraminer with no Nazi ancestors in its past.”

“Very good,” the guy says–I notice he doesn’t say “Perfect” or “Excellent”–and I stand up to collect my guest and usher him to his seat.

I have to say, for a guy who’s half a millennium old he’s not in bad shape; a little stiff in his gait, but so am I after a lot less schlepping around than he’s done in his day.

“What kind of place is this?” he asks as he peruses the menu.

“Young people trying to make it with each other.”

“What do you mean ‘make it’?” he says with a scowl.

The question tips his hand; Brant was a man of deep religious convictions and, like a lot of satirists, he has a moralizing streak that you’ll find just below the surface–if you part his hair in the right place.

“By ‘make it’ I mean that they want to fornicate with someone, and are trying to decide if their next mating partner is the person across the table from them.”

Brant: “Look at the get-up on THAT bimbo!”

“Hmph,” he hmphs with a decidedly disapproving air.

“Don’t go all prudish on me.”

“Why not? Prudery helps keep lines of descent and land titles clear.”

“Try telling that to some 26-year-old bond trader with money to burn.”

He gets down off his high horse long enough to listen to the waiter announce the specials, then says that he’ll have the lamb kebabs. I order a club sandwich and he says “What’s a sandwich?”

“They were invented after you died–really convenient. The meat and vegetables are wrapped in bread so you can pick them up and eat with your hands.”

“I always eat with my hands.”

“Well, don’t do that here . . . and now.”

“Why not?”

I explain to him that the prejudice in the early Middle Ages against dining utensils has died out. He lived under a table manners regime that considered the fork an instrument of the devil. When a Venetian princess who used one in the eleventh century died of the plague, St. Peter Damian considered it punishment by God for her vanity.

“When in Rome, do as the Romans do. When in Boston, do as the Brahmins do.”

“Fine,” he says as the waiter brings the wine to the table and fills our glasses. I’m hoping the salutary effects of the grape will get him to ease up on his irritable dogmatism, and share some of his secrets as a best-selling author who’s still read by dorks like me looking for plots to steal.

“So, you seem to have it in for just about everybody,” I say. “Do you ever get tired of dumping on people?”

“Dumping on people? You mean like dung and offal and . . .”

“No, I mean that figuratively. You write a book that’s endured down to this day but it’s basically just 112 consecutive screeds against people you don’t like.”

“I didn’t say I didn’t like them, I said they were fools.”

“Pretty much the same thing.”

“I’m in the business of making judgments.”

“I know, but some of your criticisms come across as . . . petty.”

“Like which?”

“Well, you take a shot at Innovations.”

“I was talking about men who use cosmetics.”

“But innovations in general you must be okay with, otherwise your book wouldn’t have been printed by a press with movable type.”

“Fair point. What else?”

“Number 8–‘Of Not Following Good Advice’ is a real corker.”

“What’s the matter with that one?”

“It begs the question. It assumes someone can tell whether advice is good.”

“You don’t know the difference?”

“Not always.”

“Good advice is advice you should follow. Bad advice is the other kind.”

“There you go again,” I said, channeling Ronald Reagan.

“What?”

“It’s circular. You’re just saying ‘Good advice is advice that is good.’”

“Hey–if you don’t know good advice when you hear it, I can’t help you.”

“You know,” I say, preparing to level with him, “you’re not as well known today as you were in the sixteenth century. It could have something to do with your, uh, censorious attitude.”

“Ooo–has somebody been reading Thirty Days to a More Powerful Vocabulary?”

“Don’t change the subject. You come on like you’re some kind of moral umpire, but you’re really just parroting the teachings of the Holy Roman Empire.”

“Have to say, it’s probably my favorite empire of all time.”

“What’s with the ‘probably’? Don’t you know your own mind?”

“Just a manner of speaking. Anyway, I’m trying to keep people from leaving the One True Church–is that so wrong?”

“Leaving it for what?”

“Lutheranism and Zwinglianism.”

“Zwinglianism? Never heard of it.”

“It’s a cross between Zoomba and Rastafarianism.”

“Seriously?”

“Now who’s the humorless one?”